Since Aristotle, humans have pondered the role and function of fictional narratives. Now, there is general agreement the reading of fiction builds empathy, supports our capacity for uncertainty and ambiguity, and offers new perspectives on the world.

Perhaps it is writers reaching for this combination of emotion and reflection which leads to complaints literary fiction is unremittingly bleak. But even the saddest of stories, well told, can be leavened by captivating use of language, rich portraiture and, very often, veins of humour.

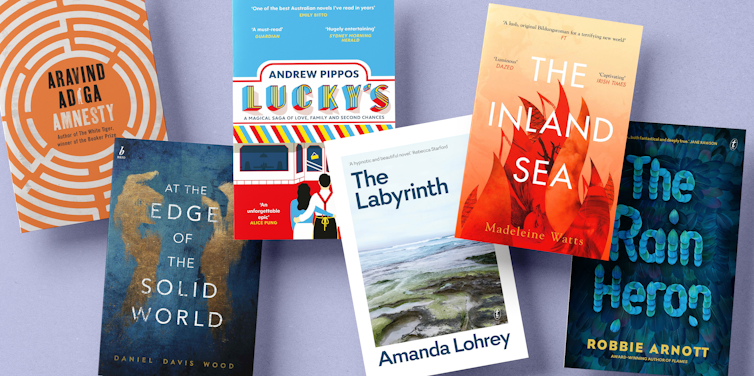

This is evident in each of the novels shortlisted for the 2021 Miles Franklin award. Here the destruction of the environment, there the abuse of refugees, and over there the despair occasioned by the everyday suffering of being human. Yet they each shimmer with energy, tenderness and threads of optimism — and even occasionally joy.

Amnesty by Aravind Adiga

Amnesty, the fourth novel from Booker Prize winner Aravind Adiga, possesses all the ingredients for unrelenting tragedy.

Danny, a young Tamil man, comes to Australia as one of the myriad international students who, pre-COVID, used to keep our economy afloat, but then drops out of what he terms this “racket” to live as an “illegal alien” with all the attendant uncertainties and anxieties.

Working as a cleaner for the rich and mostly white people of Sydney, he finds himself in possession of information about a murder and is probably the only person who knows whodunnit. The novel tracks him through a long day where, with Hamlet-Esque indecisiveness, he agonises about whether to tell the police (and expose himself to the likelihood of arrest and deportation) or to lie low (and allow a second murder to be committed).

Despite this, the novel is infused with a lightness of being and a sense of hope. Danny’s Sydney houses rats and predators, but also libraries providing sanctuary for “illegals”, his tolerant vegan Vietnamese girlfriend, his Japanese-Brazilian abseiling friend, and accommodating householders who pay him to clean their attractive apartments.

Often very funny, often deeply touching, Adiga manages to combine serious literary fiction with satire and critique. He also offers a clear-eyed portrait — or perhaps a sociology — of contemporary Australia, and of the holy grail of amnesty always floating just out of reach.

At the Edge of the Solid World by Daniel Davis Wood

In his second novel, Daniel Davis Wood weaves the complex stories of individuals and families with history and culture, space and time.

After a family tragedy, the first-person narrator of At The Edge of the Solid World gradually fractures into shards of himself.

As the novel unfolds, he unfolds, as does time. His grief is overlaid with the grief of those caught up in a current Sydney massacre, as well as the ruined cultures museumed in the songs folklorist Francis J Child attempted to save from history.

The narrator obsessively reports on every conceivable small and global disaster, spreading out across history and culture, drenching him in a lineage of loss.

The ripple effects of all the events in this account of his present are tragic, but the tragedy is enfolded in love and acts of tenderness and memory. It’s not a comfortable read. But it is an extraordinary read.

Lucky’s by Andrew Pippos

We have probably all had lunch at a place like Lucky’s, a Greek-Australian franchise offering “home-cooked” food with an acceptably mainstream menu, and where, behind the counter, a febrile life simmers away.

Andrew Pippos’ first book, Lucky’s, paints a dense and convoluted landscape spanning from the second world war through to the present.

The eponymous Lucky is a Greek-American with adequate skills on the clarinet, who impersonated Benny Goodman at a wartime concert in one chapter of a lifetime of bare competence.

Matching him is Emily, a young UK journalist who, in flight from a failed marriage, is trying to write a piece about Lucky and his doomed chain of restaurants.

Between the two people and the two periods of time, there is a large cast of well-written characters and a smorgasbord of joys and catastrophes.

The title of the book is sauteed in irony, but what could have fallen into bathos is rescued by the character of Lucky, whose loyalty and hapless charm kept me reading through to the almost-optimistic end.

The Inland Sea by Madeleine Watts

Madeleine Watts’ debut novel is set during the record-breaking Sydney summer of 2013, and a stage in the narrator’s life where “The open wilderness of adulthood stretched ahead like so much wasteland”.

In formal terms, it is a Bildungsroman — a coming of age novel — and, as expected of its genre, the narrator spends a fair bit of time in naïve narcissism, pursuing an emotionally unsatisfying affair she knows will end in heartbreak and engaging in self-destructive behaviours that alienate her friends. But there is considerably more to it than this.

The setting for much of the novel is her job at an emergency call centre, where shift after shift she surfs the tide of desperate callers from places no one knows about and for whom the emergency services will never arrive.

Read as a standard Bildungsroman, the book doesn’t deviate far from the conventions. But read as an allegory for a nation struggling to find a way into its future, Watts shifts the grounds of this genre and offers sustained narrative traction.

The Labyrinth by Amanda Lohrey

Amanda Lohrey has been recognised as a fine novelist since the late 1980s. In The Labyrinth, her eighth novel, her expertise, observant eye and ear, and sense of story are fully present.

Erica has undertaken a sea-change, moving from central Sydney to a coastal hamlet close to the prison where her son is incarcerated. She purchases a rather disreputable beachside shack with a garden large enough to contain a labyrinth. She is determined to build not just a labyrinth, but the right labyrinth: one that will deliver the promise of “reversible destiny”.

A labyrinth is a powerful trope, and here it drives not only the narrative and Erica herself but also a range of possibilities of meaning for the various characters with whom her life becomes intertwined. Though she had intended to isolate herself, the forces of kindness capture her and, gradually, she connects with those around her.

With their help, she constructs a labyrinth that is, she says, “a challenge […] to the heart”, the place where “you let go”. In her own letting go, she finds no magic solution to sadness, but rather the consolations — however temporary — of connectedness.

The Rain Heron by Robbie Arnott

Speculative fiction doesn’t often appear on literary award shortlists, which means when they are selected they are worth our attention.

Robbie Arnott’s The Rain Heron (another second novel) is set in an ecodystopia — probably not far into the future, given the current state of the planet — under military rule, where the people are simply hoping to survive.

The novel is threaded through with a strong sense of myth: the assault by capitalist imperatives on communities living in harmony with nature; the magical uncontainable rain heron; the diminished land; the woman surviving in the mountains, waiting for some sort of salvation. So far, so standard dystopia.

But this book astounds me not just for the quite brilliant conception and rendition of the eponymous rain heron, but also because of the portraits it offers: of generosity, of tenderness, of a turning toward rather than away from others. And of a plot where the deaths are caused by clumsiness or carelessness, rather than malevolence.

In a desolate social and ecological landscape, the human networks of compassion make this novel a thing of rare beauty.

The winner of the 2021 Miles Franklin literary award will be announced at 4pm AEST today.

Jen Webb, Dean, Graduate Research, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.